“To depict the body is to depict humanity”. — Emma Lavigne

The body is a major subject in art history, and it has often been depicted according to conventional canons. But how is it portrayed today? Emma Lavigne, curator of the exhibition "Corps et âmes", ponders this question.

Why the body?

The body is an omnipresent subject throughout art history. There have always been attempts to depict it, since the very dawn of humanity, with handprints that might have been an early way of making art with one’s own body. Almost half of the works in the Pinault Collection deal with the issue of portraying the body. These contemporary artists, however, are not as concerned with depicting the human body in the most realistic manner possible as they are with expressing an emotion and sense of engagement that is often political. The body thus becomes a medium for another kind of narrative that is trying to take the pulse of the world. What unites all the artists in this exhibition is their use of the body as a kind of medium, a seismograph that has just recorded the world’s tremors in an attempt to portray people in terms of life, humanity, thought, and the soul that inhabits most of these depictions.

Some artists use the body to bear witness to History and to the violence of this world. What form does this take?

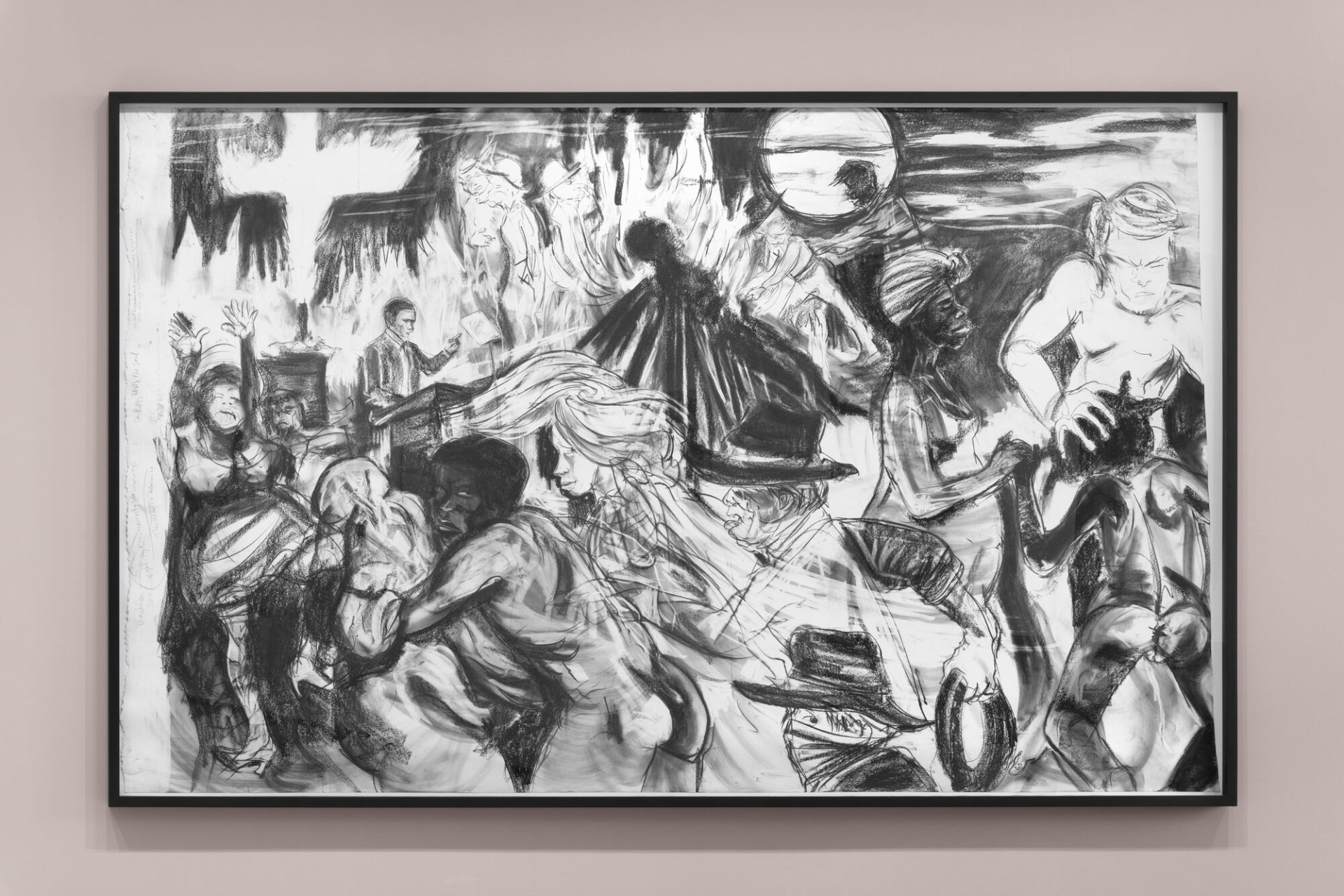

Many artists come up with a new way of telling a story that we don’t want to see. Consider, for example, the eminently political work of Kara Walker. We have featured a very large drawing by this artist in this exhibition that emulates the scale of a historical painting, except that it’s a drawing that one could almost erase. With extreme rapidity, Walker draws scenes that are barely distinguishable due to the movement of these abused, black bodies and this creates a kind of chaos. The only vertical, balancing element in this chaotic composition is the figure of Barack Obama giving his famous speech on race, in which he talked about his African origins and the United States’ responsibility in the history of slavery. Art thus becomes a kind of witness to the violence of this world, which some individuals continue to suffer.

“What unites all the artists in this exhibition is that they use the body as a kind of medium, a seismograph that has just recorded the world’s tremors in an attempt to depict humanity”.

Can art also free the body?

Another key piece in this exhibition is a sculpture by Niki de Saint Phalle. Starting in 1965, she created a variety of nanas noires, extremely joyous and almost acrobatic figures with extremely flexible and malleable bodies. But what is especially interesting about her work is its profoundly political dimension. Niki de Saint Phalle greatly admired Billie Holiday, with whom she shared the painful experience of incest. She made a nana noire figure in homage to the singer, but she was also very inspired by Rosa Parks. The nana noire featured in the exhibition represents one of the very first representations that the artist dedicated to these black women, to whom she wished to pay tribute.

What is the role of music in this exhibition?

Music is very present in the exhibition. It can be silent, as in the extraordinary hand that represents the body and soul of Miles Davis, as photographed by Irving Penn. But it is also audibly present: there are small listening booths in which visitors can listen to a two-hour-long playlist compiled by Vincent Bessières that exists in resonance with the works in the exhibition. You can hear Miles Davis, of course, along with Jimi Hendrix, Aretha Franklin, and even texts read aloud by James Baldwin. A number of artists in this exhibition, such as Kerry James Marshall and David Hammons, draw their inspiration from jazz in its many forms, especially free jazz. It’s fascinating to see just how much the performing arts (music and dance) have been preserved in the depths of our memory and then feed other forms of artistic expression, such as sculpture and painting. These are also the roots underlying certain practices by these African American or Brazilian artists that we aimed to activate in the exhibition.

“It’s fascinating to see just how much the performing arts of music and dance fed other artistic practices”.

How does Arthur Jafa’s work fit into this exhibition?

Jafa’s work shares this completely universal dimension with Black American music. At the very centre of the exhibition, in the Rotunda, a space that is very symbolic of the museum, we wanted to feature his film Love is the Message, the Message is Death. This iconic work looks at the stances that have been taken on the black body since the nineteenth century. The film is a message of peace and hope; it is also an homage to the African American community. It shows scenes of violence, especially at the hands of the police, alongside moments of hope. We see Barack Obama, as well as Miles Davis, James Brown, and Jimi Hendrix. This utterly overwhelming composition, in which, alongside the violence inflicted on the African American community, we see the power, exorcism, and the cathartic power of African Music, makes Love is the Message, the Message is Death a deeply socially engaged work that pushes us to think and compels us to acknowledge this violence.

Read the interview with Arthur Jafa

Can you tell us about Georg Baselitz’s monumental bodies at the end of the exhibition?

The exhibition concludes with Baselitz’s extraordinary cycle Avignon, which he painted in 2015 for the Venice Biennale. Eight paintings hang in the space feature eight self-portraits of Baselitz emerging from the darkness. The body is not at all idealised here, as it is throughout the history of painting; what we instead see here is the artist’s aging body. We are confronted with these bodies that fall, that dance with time in an almost macabre fashion. And the paint spurts, trickles, becoming almost like blood or lymph, almost a living substance, as if he were painting with the last bursts of strength of his body. So, what is ultimately interesting about this work is not so much its monumentality as the artist’s humanity that imbues the entire painting.

The exhibition Corps et âmes is open until 25 August 2025 at the Bourse de Commerce — Pinault Collection in Paris.