"I became interested in this history because it seemed to offer a new way of approaching the 1980s" — Clara Royer

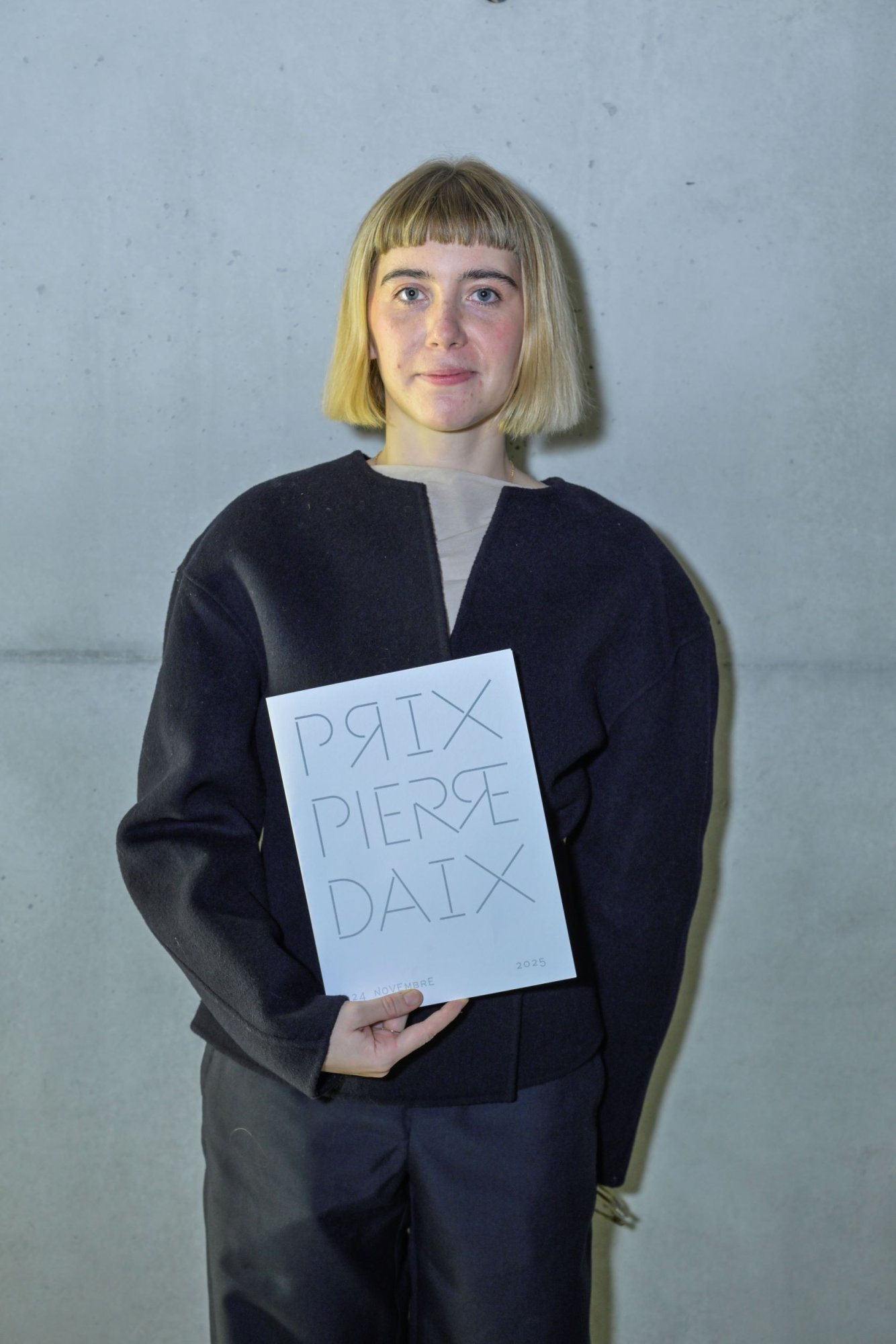

As the first recipient of the Bourse Pierre Daix, Clara Royer explores the relationship between art and telecommunications in the 1980s and explains its resonance with our present time.

On the occasion of the tenth anniversary of the Prix Pierre Daix, François Pinault wished to create a parallel grant designed to support and accompany the writing of young art historians. For its first edition, it has been awarded to the researcher Clara Royer.

How would you define telematic art, and why were you drawn to this particular field?

Telematic art refers to a set of experimental practices that, in the 1980s, explored computer-based telecommunications networks as materials, media, and spaces for artistic creation. In concrete terms, this took the form of images, sounds, texts, and gestures exchanged through a range of technologies—from satellites to Minitel—within collective actions carried out simultaneously in different parts of the world. In the most spectacular cases, one encounters genuine tele-performances bringing together dozens of participants interacting remotely through screens. But whatever the configuration, what matters most is that the aim is less to represent the network than to experience it. In this sense, the sending, circulation, and reception of data constitute the artistic process itself. The work does not present itself as an object or an image, but as a relational situation whose core is the very act of transmission—the state of being connected, of experiencing mediation.

I became interested in this history because it seemed to offer a new way of approaching the 1980s, a decade too often reduced to a period of stagnation or apathy. Telematic art, however, reveals a very different narrative: that of an international avant-garde which, from Vienna to Vancouver, Santa Monica to São Paulo, Łódź to New York and Dakar, via the Fiji Islands and Hokkaidō, was empirically inventing an early form of networked culture. Tracing the footsteps of this movement forces us to reconsider the decade as a pivotal moment, situated between the legacy of the great modernist project and the emergence of a postmodern condition—of which telematic art was, in a way, a Trojan horse. In fact, the very notion of “telematics,” understood as the convergence of telecommunications and computing—and popularized by the influential 1978 Nora-Minc report—crystallizes this shift. For thinkers such as Jean Baudrillard, Jacques Derrida, Vilém Flusser, and Félix Guattari, it served as a framework for imagining an imminent world structured by the accelerated circulation of information, the networking of knowledge, and the proliferation of flows on a global scale. And this new regime was not merely accompanied by telematic art—it was given a sensory expression through it, making the field both witness and laboratory.

How do your research interests connect to this network of artists and these media?

My research focuses on a network active between 1977 and 1991, organized around one technology in particular: slow-scan (or slow-scan television), a kind of ancestor of contemporary videoconferencing that, for more than a decade, crystallized an entire generation of artists’ fascination with the globalization of image circulation. Drawing on around fifty archival collections, I retraced a dense web of experimental connections—stretching from the Americas to Western Europe and across the Pacific Basin—within which a constellation of practitioners emerges, engaged in a play of intersecting, and sometimes unexpected, collaborations: Mona Hatoum meets Valie Export, Aldo Tambellini works with General Idea, Otto Piene and Nam June Paik with Julio Plaza, Liza Béar and Willoughby Sharp with Carl Loeffler, Richard Kriesche with Robert Adrian X…

But my work does not stop at mapping these exchanges. More broadly, it seeks to understand what drove them. What was at stake behind this frenzy of connections? What does it reveal about its historical moment? My hypothesis is that it responded to a broader transformation of the global order, marked by the growing deregulation of flows—of goods, services, labor, and capital, but also, and above all, of information and images. Artistic uses of slow-scan were both a product of this shift and a critical mirror held up to it.

Curiously, these issues—which shaped the final decades of the 20th century and helped form today’s digital culture—have remained largely peripheral in art history. When it has not simply ignored them, historiography has reduced telematic art to a form of naïve techno-romanticism, attributing to its actors the belief that the union of art and telecommunications could abolish social, linguistic, and ideological barriers. Blissful ignorance, in short—of both the infrastructural and systemic obstacles to establishing a “global village” and the risks inherent in realizing such a utopia, from cultural homogenization to high‑tech imperialism and electronic colonialism. The investigation I conducted reveals quite another reality. Far from embodying a pacified ideal, telematic art emerged in resonance with the Global South’s demand for a New World Information and Communication Order (NWICO), whose manifesto called for a more equitable international distribution of frequencies—at a time when nearly 90% of the spectrum was monopolized by countries representing less than 10% of the world’s population. In this context, slow-scan functioned for artists as a regulator: a means of negotiating, diverting, and making visible the asymmetries and violences of the network.

My aim is therefore not only to reconstruct the history of a forgotten medium, but also to situate its stakes at the heart of the conflicts that, on the threshold of the new millennium, made connectivity an essential condition of power. In doing so, I hope to offer a critical archaeology of the Internet while bringing to light the role of slow-scan in shaping the globalized future of art.

« My aim is therefore not only to reconstruct the history of a forgotten medium, but also to situate its stakes at the heart of the conflicts that, on the threshold of the new millennium, made connectivity an essential condition of power. »

How does this little‑studied art form resonate with our contemporary moment?

Because it lays bare—at an early, still‑experimental stage—the very logics that structure today’s circulation of images and data: the illusion of universal connection, the intuition of its structural violence, the concentration of infrastructures, the blurring of participation and control, data extractivism, and informational capitalism. At the same time, telematic art makes visible what we now take for granted: the fact that every relationship, every image, every interaction passes through devices. Whereas today’s uses tend to naturalize technical mediation—rendering it transparent, almost imperceptible—artistic uses of slow‑scan insisted, on the contrary, on its frictions, delays, glitches, approaching communication not as an immaterial and instantaneous flow but as a situated process, tightly conditioned by protocols.

For all these reasons, telematic art offers valuable tools for thinking about our digital present not as a natural or inevitable horizon, but as the result of technical, cultural, and ideological choices that could have been articulated otherwise. In this sense, artistic uses of slow‑scan constitute the tangible trace of a moment when the network was not yet fixed, but remained a space to be negotiated. Other architectures were possible.

How do you envision developing your project in the coming years?

I am currently working on my dissertation, the first step in a long‑term research project. Some parts of it have already been published, notably in the Cahiers du musée national d’art moderne, and other articles will be appearing very soon. Ultimately, I would like to develop this work into a book that would position telematics not only as an essential observatory of our connected contemporaneity, but also as an entry point for a global history of art attentive to its technological mechanisms.