Prix Pierre Daix 2025

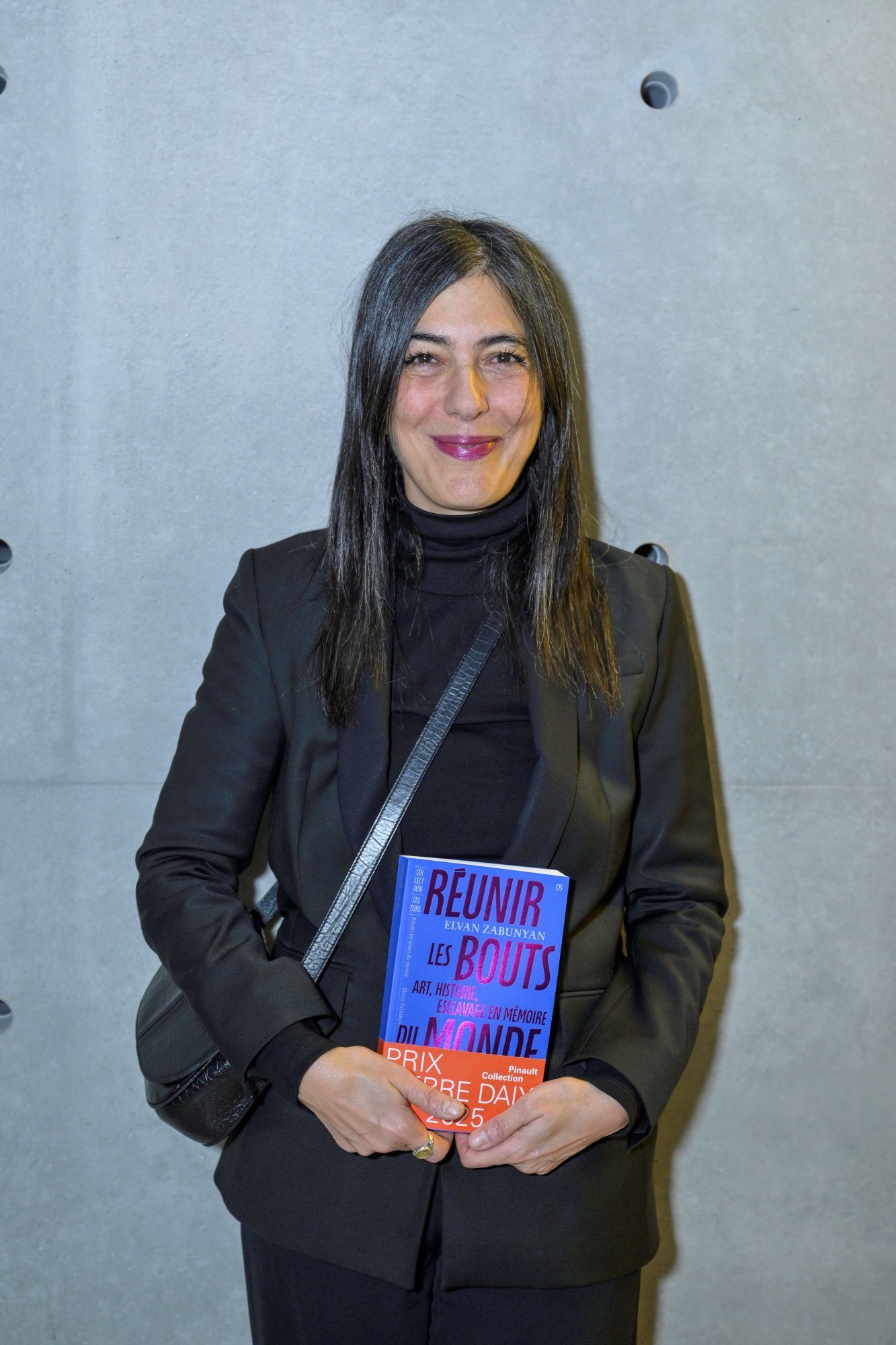

The 2025 Prix Pierre Daix was awarded to Elvan Zabunyan on 24 November 2025 at the Bourse de Commerce by François Pinault.

Pinault Collection is pleased to announce that the Prix Pierre Daix is being awarded this year to Elvan Zabunyan for her work Réunir les bouts du monde. Art, histoire, esclavage en mémoire, published in October 2024 by éditions B42, as part of its “Culture” series.

The Prix Pierre Daix was created by François Pinault in 2015 in memory of his friend, the writer and historian of French art Pierre Daix, who died in 2014. A militant, resistant free spirit and major intellectual figure of his time, Pierre Daix was a specialist in twentieth-century art and author of a number of works that shed considerable light on the artistic movements in which he had taken an interest.

Each year, the Prix Pierre Daix is awarded for a book on modern and contemporary art. On this its tenth anniversary, the prize was increased to €15,000.

The jury, which is composed of ten figures from the world of art and academia, has awarded the prize for the book Réunir les bouts du monde. Art, histoire, esclavage en mémoire by Elvan Zabunyan, a highly innovative piece of writing that is part literature, part essay, and part history, all the while expressing a political approach. The author celebrates major figures of the African American and Caribbean art scene such as Arthur Jafa and Frank Bowling (both included in the Pinault Collection) and situates them within a historical and cultural continuum that has long remained overlooked. Elvan Zabunyan’s research proved influential for the conception of the exhibition ‘‘Corps et âmes’’ held at the Bourse de Commerce from March to August 2025. The themes addressed in her book will also resonate strongly with the four exhibitions that will be held at the Pinault Collection’s museums in Venice in 2026: Michael Armitage and Amar Kanwar at Palazzo Grassi, and Lorna Simpson and Paulo Nazareth at the Punta della Dogana.

The book

Réunir les bouts du monde discusses visual, literary, musical, and critical works from the United States and the Caribbean that carry within them a memory of the transatlantic slave trade. The history of slavery did not stop with its abolition. It has instead been perpetuated through racism, segregation, lynchings, imprisonment, and the social, cultural, political, and policing repressions in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries in countries with a legacy of slavery.

In her analysis of the artists, writers, and intellectuals who have based their practice on the irreversible rupture caused by four centuries of the Triangular Trade, Elvan Zabunyan looks at what this history continues to produce in the present day. The persistence of vestigial memories of the slave trade and their transmission drive all of these artistic creations, which approach the question of dispersal and fragmentation from a decidedly aesthetic and poetic perspective. Zabunyan views the back-and-forth movements through space and time, as well as the omnipresence of a past that sheds light on the present as embraces imbued with affect, which makes the art history she writes a situated, sensitive, and engaged narrative.

Author biography

Born in Paris in 1968, Elvan Zabunyan is a contemporary art historian, art critic, and professor at the Sorbonne in Paris. Since the mid-1990s, she has produced an art history that explores the historical, political, post-colonial, and feminist aspects of art in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, especially in the United States. She is the author of the pioneering work Black is a color, une histoire de l’art africain-américain (Dis Voir, 2004) and the first monograph on Theresa Hak Kyung Cha (Les presses du réel, 2013). She is a member of the editorial board of the journals Esclavages et post-esclavages (CIRESC/CNRS) and Critique d’art (Rennes). She has contributed to artist’s publications including Lorna Simpson (Prestel, 2013), Adrian Piper (MoMA, 2018), Ellen Gallagher (WIELS, 2019), and LaToya Ruby Frazier (Mudam, 2019). She has coedited a number of works, written many articles for anthologies, exhibition catalogues, and periodicals in France and abroad.

Works that she has coedited include Constellations subjectives, pour une histoire féministe de l’art (Ixe, 2020), the result of a conference on feminist subjectivities in contemporary art, held at the University of Rennes 2, where she taught for twenty-four years; Decolonizing Colonial Heritage, New Agendas, Actors, and Practices in and beyond Europe, published by Routledge in 2022 as the outcome of the European research programme ECHOES (European Colonial Heritage Modalities in Entangled Cities), for which she coordinated the “Artists and Citizens” Work Package between 2018 and 2021 (which included the cities of Marseilles, Bristol, and Capetown); and L’art en France à la croisée des cultures (Paris/Heidelberg, DFK Paris/arthistoricum.net, 2023).

In 2024, she was visiting professor at University of Zurich, where she taught in the “Art History in a Global Context” programme. In the autumn of that same year, she co-curated the exhibition ‘‘Correspondances, lire Angela Davis, Audre Lorde, Toni Morrison’’ at CREDAC in Ivry-sur-Seine, which was based on research she conducted in the archives of these three authors in the United States. The work she co-edited as part of the series “Histo-art” titled Vaincre le silence, histoire de l’art et genre was published in June 2025 by Éditions de la Sorbonne. Zabunyan is the co-editor of the book Echo Delay Reverb, art américain et pensée francophone (B42, October 2025), which accompanies the exhibition of this same name at the Palais de Tokyo this autumn.

Interview with the author

What are the correspondences in your book between the concepts of art, history, and slavery?

“Art, history, and slavery in memory” is the subtitle of Réunir les bouts du monde. I would like to emphasise that art reveals new resonances when it looks at the history of slavery, such as the connections that artists form with the past and with archives, the power of the transmission of memory, and the working methods that I applied. My research focuses on an in-depth analysis of what artists produce. I look at history, the history of slavery in particular, through the prism of art. Going back to the nineteenth century, I studied the abolitionist struggles before and after 1865, the date in the United States that marked the emancipation of enslaved peoples at the end of the Civil War. I work with an awareness of a past that permeates contemporary art.

I am interested in the way that artists represent the historical facts of this era in and through their work, through a process of creation rather than of illustration. As an art historian, I explore what these works convey. I look at them, listen to them, immersing myself in the imaginary worlds they compose and the freedoms they offer. I think that your use of the term “correspondences” appropriately describes how I wrote this book. It was the many artistic correspondences that helped me weave connections between the empty spaces and the silences in the history of slavery.

Why did you become interested in the American and Caribbean scene in particular to explore this topic?

My work has focused on African American art for the last thirty years. I read my historical, theoretical, critical, philosophical, and artistic sources mainly in English. I admire the work of colleagues who study similar subjects in South America, Africa, and the Indian Ocean. For my entire career, I have conducted most of my research in the United States, working directly with the artists and intellectuals who live there. I also discovered the Caribbean from Great Britain and France. In discussing the works of artists and writers from the Antilles, Guyana, Jamaica, and Cuba, I have emphasised the phenomena of cultural displacement and the conversations that result from them. My research focuses on what we call the “African diaspora”. Four centuries of deportation of several million people from Africa to the Americas during the Triangular Trade and the ensuing loss of origins has always affected me greatly. This is a central concern in my studies.

From there, I brought together works by artists who used the memory of this irreversible experience as material for their creative process. I also wanted to show that the works arising from their respective reflections manage to propose new forms, that the fragmentation caused by the destruction of one’s origins creates new aesthetics. In my dedication to the work of certain artists and theoreticians with whom I have formed strong bonds over the years, I wanted the research for this book to be situated intuitively within the continuity of my thinking, and for it to confirm and strengthen these bonds. I intentionally created unexpected passages and meeting points between works and artists. I also generated a major methodological rupture by not considering the American and Caribbean artistic scenes as separate, instead as tied by a collective history of dispossession and violence, by a shared heritage that grants them an immense power of revolt and emancipation.

How did you assemble this book and what was the reason for these unique chapter titles that refer to natural elements?

The book’s composition is transversal and transhistorical. It was conceived as a trajectory based on the experiences of enslaved people and the tribute that artists have paid to them. It was built using books that I had chosen to include in my thinking about this topic. This was a necessary process, because I had collected a large number of artistic references in ten years of research, and I couldn’t incorporate them all in the book without interrupting the non-linear movement that I had opted for. Everything, from the first epigraph to the final quote, was envisioned well in advance, in a highly precise manner, but at the same time, I chose to give the content a certain flexible organicity. I thought of the reference to the natural elements at least five years before I began writing the book. I had to find a way to organise my archives, and I quickly saw that water, earth, fire, and air allowed me to study these works without confining them to a thematic approach.

As is very clear in the book, this chapter structure opens rather than closes. We can feel the works taking us by the hand, helping us move through this history which bears the memory of slavery. I also began researching artists very early on who had used the biographies and autobiographies of people who had been enslaved and who had fled the plantations to tell their life stories. In this way, figures I discovered and came to admire—Harriet Jacobs, Frederick Douglass, Sojourner Truth, Harriet Tubman—became, through their writings and photographs, precious subjects for the contemporary artists who invoked them. So, I decided to begin with a first chapter that I titled “Intertwined narratives”, which emphasises processes that combine nineteenth-century history with contemporary art history. The works themselves also led to the reference to the elements. Water became the title of the second chapter because many artists have used it in their visual practice as a metaphorical interpretation of crossing the Atlantic, also known as the Middle Passage. This opens the door to paradoxical imaginary worlds that comprise everything from the immeasurable violence of what transpired on board the slave ships to their ensuing poetic representations.

A very important author who expressed this concept was Edouard Glissant, with his notion of the “open boat”, which he describes in the very first pages of his book Poétique de la Relation, published in 1990. He narrates the horror that the enslaved passengers lived through during their voyage of no return, being stripped of absolutely everything they had and were, and the feeling of survival that came out of that. Through his unique language, he provides more tangible ways of understanding this legacy than what historians have offered. I approached the three other elements in a similar manner: earth as the arrival in a foreign land and an existence in resistance, fire as a symbol of ancestral beliefs and the blaze of revolt, and finally, air, which invokes the sky and the stars which slaves used as a compass, all the while alluding to the fact that the oxygen we breathe can vanish and lead to asphyxiation. At every step, the artworks that I have brought together reveal hidden sensations and realities that are both political and poetic. I then placed them alongside historical facts and contextual elements that I consider necessary.

What was your experience of writing this book, and what role does literature play in the research that you have conducted?

It was in fact an experience to write it. As I wrote, I could feel the galvanising effect of conveying through words both my research and the emotions I experienced while carrying it out. The relationship between a critical approach to the artworks and the desire to retrace obscured aspects of history took the form of a socially engaged kind of writing. When I reread certain passages, I see it as expressing an urgent need to express my thoughts and ideas. Several people who have read the book have compared my writing style to literature because I took certain kinds of liberties in my writing that are unconventional in academia. I am first and foremost an art historian, and I don’t think of myself at all as a writer, in the sense that my book is in no way a work of fiction, even if I use that as a leitmotif when I point out that artists use fiction to narrate the original history of slavery, which I have in turn studied and contextualised.

This leads me to say that literature plays a primary role in my work because it taught me how to read between the lines to grasp the abominable reality of slavery as an institution. I read Toni Morrison’s Beloved in the early 1990s. Together with Octavia E. Butler and her novel Kindred published in 1979, Morrison was one of the first writers to translate the horror and violence into a language of incredible beauty, to create an imaginary world for what Patrick Chamoiseau would call the unthinkable. In 2016, Chamoiseau published his book La Matière de l’absence. When I read it, I felt all kinds of connections with what I wanted to do in my book: the possibility of summoning facts through the evocations of poets and artists. I met Chamoiseau at a conference in Rennes several months later, and I had the opportunity to talk to him about my research. To converse with a writer who used Glissant’s Poétique de la Relation as one of several possible ways to imagine the world in all its differences proved another important moment in my writing process. I chose the freedom to express myself as I saw fit. I could cite many other writers who accompanied me throughout my research: Audre Lorde, James Baldwin, W.E.B Du Bois, a sociologist whose writing is very literary, and especially Michelle Cliff, an author of Jamaican origin who is also an art historian, whose works helped me embrace my sensitivity even more fully to the subject that I was working on.

How do you think your book contributes to a new interpretation of art history and its resonances in contemporary art?

As with any long-term research, I tested my ideas over the years in seminars, lectures, and articles. I presented some of my works in the classes I teach at university. At the same time, the exhibitions we see these days confirmed that my hypotheses and intuitions were aligning with a growing desire to refocus our attention on artistic and cultural productions that explored problems of race and issues of colonial history and slavery with an ever greater rigor. Museums in Brazil, the United States, Great Britain, the Netherlands, and France have chosen to showcase artistic practices that are directly concerned with these problems. In 2024, several months after I had turned in my manuscript and the book went into production, I saw Entangled Pasts, 1768-now at the Royal Academy of Arts in London, an exhibition featuring works that I had written about, specifically ones by Frank Bowling, Ellen Gallagher, John Akomfrah, and Isaac Julien, and which had opted for resonances similar to mine.

So Réunir les bouts du monde is an attempt to give greater breadth to art history. I often mention the notion of elasticity when I talk about ways to overcome academic constraints and gain a greater freedom in the way that we interpret works. Since the book has come out, I have seen that art history students who have read it have themselves opted for more emancipated research methods, momentarily setting aside the imperative aspect of objectivity to express their own subjectivity through a rigorous study of artworks. The transatlantic slave trade is a history of genealogical ruptures, and contemporary artists are re-forming unknown connections and resuscitating vanished memories. I’m delighted if this book helps encourage this trend.

Members of the Prix Pierre Daix jury

The jury for the Prix Pierre Daix and the Pierre Daix Bursary is chaired by Emma Lavigne, General Director and Chief Curator of the Pinault Collection.

— Laure Adler, Journalist and author

— Jean-Louis Andral, Art historian and critic, Director of the Musée Picasso d’Antibes

— Martin Bethenod, Chairman of CREDAC and Chairman of the Archives de la critique d’art

— Nathalie Bondil, Art historian, Director of the new department of the museum and exhibitions at the Institut du Monde Arabe

— Jean-Pierre Criqui, Curator of the contemporary collections, National Museum of Modern Art / Centre Pompidou, editor-in-chief of the Cahiers du Musée national d’art moderne

— Cécile Debray, Art historian, Director of the Musée Picasso, Paris

— Donatien Grau, Historian of French art and literature, critic, and writer

— Christophe Ono-dit-Biot, Adjunct Editorial Director of the weekly magazine Le Point, writer

— Bruno Racine, Director of Palazzo Grassi—Punta della Dogana, writer

— Pascal Rousseau, Historian of modern and contemporary art, recipient of the Prix Pierre Daix in 2020