"Tatiana Trouvé and Italo Calvino: The Inexhaustible Surface of Things" by Bruno Racine

Trouvé’s necklaces bring to mind the city of Clarice, which passes through an indefinitely repeating cycle of collapse and rebirth, forcing the survivors to rummage through the ruins, collecting and patching them together

[…]

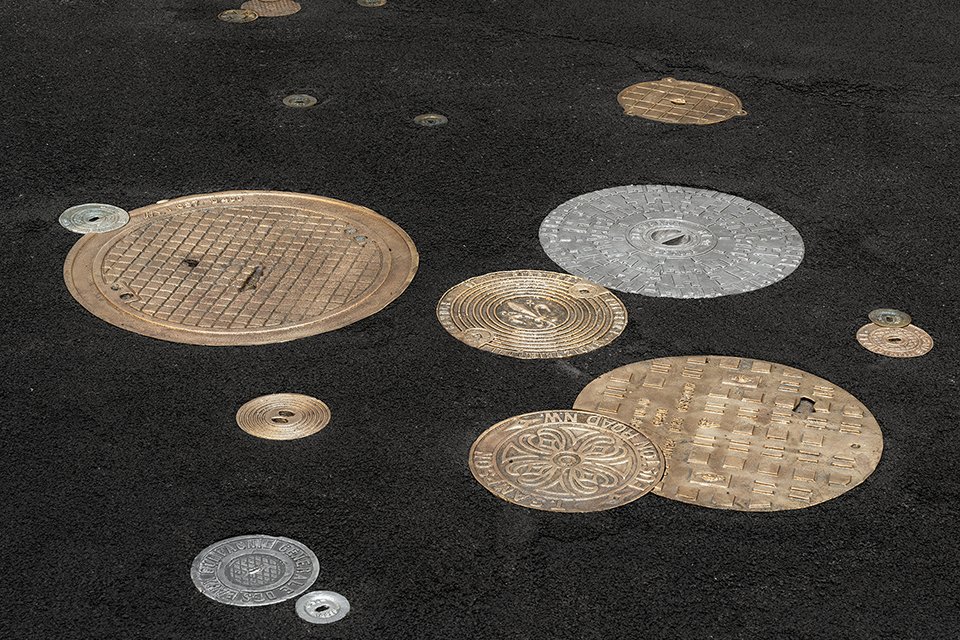

One of the first rooms in the exhibition contains “city necklaces” made up of a mass of disparate elements Trouvé has gathered while walking in places all over the world. Rather than the original found objects, faithful reproductions in bronze, copper, and aluminum have been strung together. They include a remarkable number of little silver capsules, copies of those used for doses of methadone in New York, which users then discard in the street. Like the walnut in the folktale whose cracked shell gives access to an endless bolt of fabric, each one of these capsules is the origin point of countless possible stories, a “Workshop for potential narratives.” Where and when did Trouvé pick it up; what was she thinking about at that very moment; what happened to the user who threw it away once it had been emptied; what happened to the dealer…? Trouvé has written, “all the materials I use come full of ideas and stories.” She adds: “The lives of my Guardians will always remain to be imagined.” (3) This applies equally to Trouvé’s archive, where the most diverse objects have been arranged in families over a vast system of shelves: leather sacks, cigarette lighters, dried flowers, transistor radios, telephones, cameras, cans, etc., all in metal reproduction, most often bronze, an alloy that has been used since Antiquity for the most prized sculptures, lending them an air of imperishability. In a striking passage, the Khan of the Tartars imagines that his dialogue with the young Venetian is nothing but a dream, that they are really a pair of “beggars”: “as they sift through a rubbish heap, piling up rusted flotsam, scraps of cloth, wastepaper, while drunk on the few sips of bad wine, they see all the treasure of the East shine around them.” (4) Transfiguring discarded objects into a precious and durable material turns this dream into reality. In the same way as the city necklaces, the archive exhibited in Venice constitutes a journal, like all collections do—as Calvino observes: “a diary of travels, of course, but also of feeling, states of mind, moods.” (5) Tatiana Trouvé’s collections, characterized by accumulation and classification, are a pendant in the visual arts to the writer’s journal, both of which begin with “that obscure mania that urges us as much to put together a collection as to keep a diary, in other words the need to transform the flow of one’s own existence into a series of objects saved from dispersal, or into a series of written lines abstracted and crystallized from the continuous flux of thought.” (6)

Trouvé’s necklaces bring to mind the city of Clarice, which passes through an indefinitely repeating cycle of collapse and rebirth, forcing the survivors to rummage through the ruins, collecting and patching them together, “like nesting birds.” (7) Each new Clarice “shows off, like a gem, what remains of the ancient Clarices, fragmentary and dead.” (8) Trouvé’s casts of found objects, made in a material that protects them from decay, are concentrations of time, a time that can extend well beyond the duration of human life. “When I see a stone,” she writes, “I see how a world has been sedimented.”(9) Both the artist and the writer share the awareness that in their respective works, “desires are already memories,” as Marco Polo puts it melancholically.(10)

[…]

--

3. Trouvé, Atlas, 253.

4. Calvino, Cities, 104.

5. Calvino, «Collection of Sand,» in Collection of Sand, translated by Martin McLaughlin (Mariner Books: Boston, 2013), 6.

6. Calvino, «Collection», 7.

7. Calvino, Cities, 106.

8. Calvino, Cities, 107-8.

9. Trouvé, Atlas, 249.

10. Calvino, Cities, 8.

Excerpts from the catalogue of the exhibition "Tatiana Trouvé. The Strange Life of Things" at Palazzo Grassi