"My sculptures, my installations, and my drawings always resonate with echoes" Tatiana Trouvé

Tatiana Trouvé in conversation with Caroline Bourgeois and James Lingwood

Caroline Bourgeois and James Lingwood — Could you tell us about the quote from Astrida Neimanis that you have pinned to the wall of your studio, “The water that is in your body now was perhaps a river before, perhaps it was part of an ocean before”?

Tatiana Trouvé — I like this quote a lot. The water that is in our bodies means that we are aquatic beings, that we come from water, but also that we will return to water and that our death is an evaporation. The water within us will circulate and—as long as we aren’t enclosed in a coffin—perhaps it will nourish the roots of trees that in stretching up into the clouds induce the rain to fall. Our water will flow into other waters, joining streams, rivers, seas, the living world. It’s an aquatic symbiosis within the cycle of life, which on a metaphysical level, as Deleuze says, implies that “it’s organisms that die, not life.”(1)

CB/JL — How does this inform the way you’ve envisaged the exhibition at Palazzo Grassi?

TT — The entire exhibition is linked to this dynamic, this regeneration, to displacements and transformations so what appears in one place can reappear differently elsewhere, in a cycle that is like life. More literally, the work in the atrium of Palazzo Grassi is also linked to the phenomenon of the circulation of water. Visitors walk over an asphalt floor embedded with drain covers in stone and metal as well as other elements from the street such as zebra crossings and metal covers for various utilities. The composition is a kind of imaginary map where water is present but invisible, in contrast to Venice where water is everywhere and visible. This map signifies that all the waters of the world converge at a single point, and that this point is everywhere—like here beneath our feet, in Venice. I also liked changing the perspective of the visitor through a shift in scale (since from the body to the ocean, water also moves from one scale to another), so when viewed from the floor above, the atrium floor is transformed into a constellation. Between a floor covered in drain covers that takes us underground and a view from above that leads us to the sky.

[…]

CB/JL — Can we think about all your work as a kind of ecosystem?

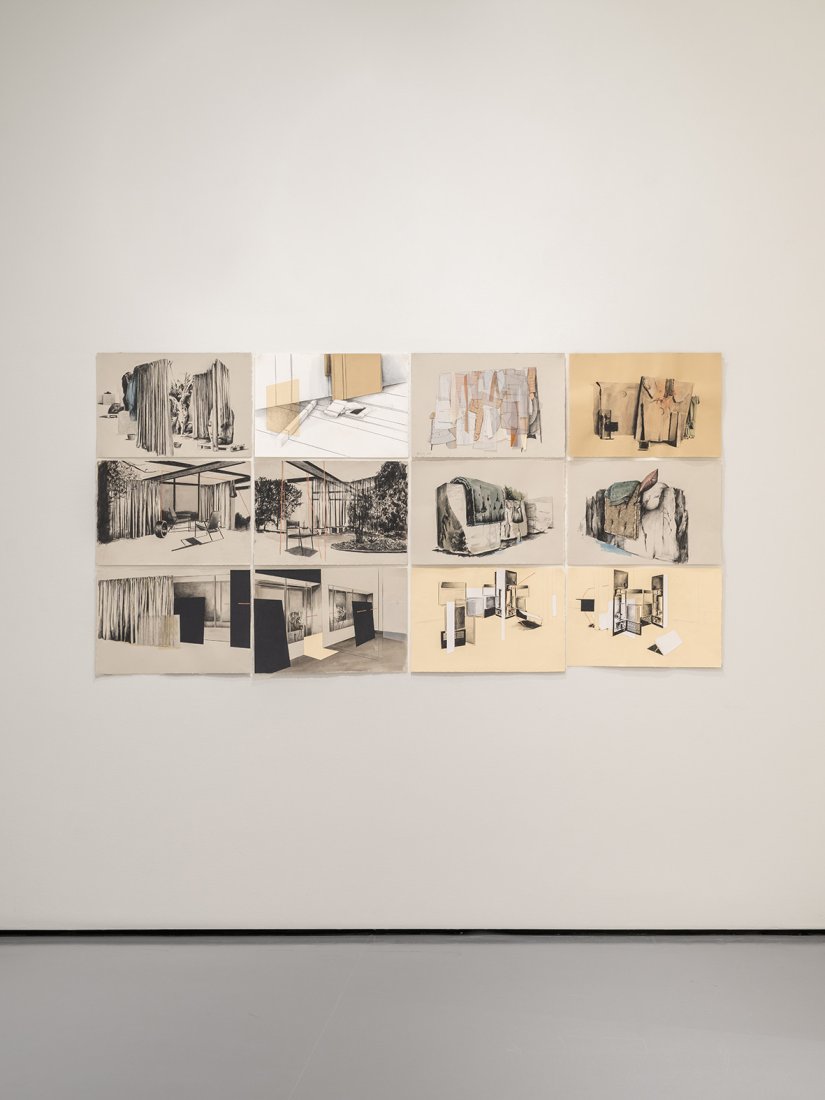

TT — The circulation of the various elements that make up my work is very dense. The things I make are all connected to one another to some degree. I don’t distinguish between my sculptures and my drawings, and I’ve always made sure there is some cross-over between them. The sculptures can draw the space in which they are placed, and the drawings can sculpt the spaces in which they’re exhibited. But there are also elements that can circulate between them: materials, forms… Altogether, they make up a sort of ecosystem. I came up with the term echo-system to describe this, since my sculptures, my installations, and my drawings always resonate with echoes, there is an echoing relationship.

CB/JL — Most of the objects you use in your work have a history. They belonged to a city, a person, a body. How important to you is this idea of recuperating or re-making something that has existed somewhere else?

TT — Over time, I have developed a practice of collecting objects: scraps and fragments of things which carry traces of time through accidents, alterations or the way they were used in their previous life. I’ve put together a sort of atlas of these objects realized in different materials—bronze, metal, stone, cement, plaster, and foam—which have travelled with me for years now. When they’re reproduced in other materials, they are transformed and become part of the ecosystem of my work. The identity of the objects can change, and they can feed into new narratives, where they respond to one another. They turn up in sculptures or installations, but they can also just sit on the shelves of my studio for years. It’s as if they have a life of their own.

CB/JL — Some objects have recurred in your work for many years, for example, women’s shoes, blankets, suitcases, keys. What is their significance to you?

TT — What these objects have in common is a relation to a world in movement. Shoes evoke the idea of walking and thinking; suitcases, blankets, and cushions have an association with dwelling and travelling; keys suggest the possibility of opening and closing, of passing from the inside to the outside. For me, these objects are links, building blocks for narratives, even if what the narratives do is make us lose our way. The objects are recurring elements which open my work to many different stories that lead to other worlds. Worlds that are not my own, that are related to thoughts beyond the boundaries of my own practice. This can be seen in another group of objects, where the titles of books by authors that have enriched me are engraved on stone books. The movement of the elements in my work is subtle rather than fast, but nothing is still; even the materials I use most often are not stable, contrary to what is normally thought: bronze oxidizes continually over time, and can become diseased; stone carries a history within it that slowly erodes. The disorder in the work is linked to the overlapping of these multiple movements.

[...]

(1) Gilles Deleuze, "On Philosophy", in Negotiations: 1972-1990, translated by Martin Joughin (New York: Columbia University Press, 1995 [1990]) 143.

Excerpts from the catalogue of the exhibition "Tatiana Trouvé. The Strange Life of Things" at Palazzo Grassi