"Each epoch dreams of the next" by Matthieu Humery and Andrew Cowan

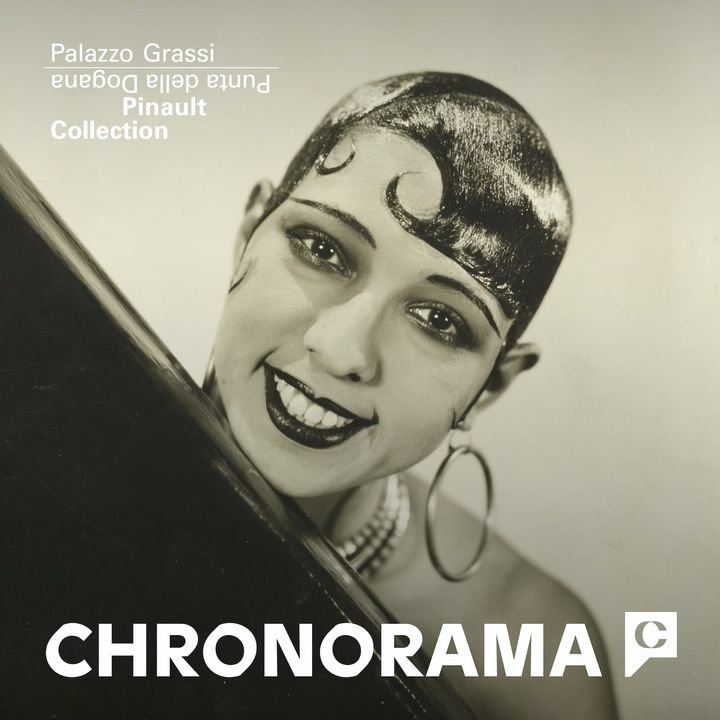

Four hundred and nine works, from 1910 to 1979, presented chronologically and by decade, illustrate the men, the women, the moments in history, the daily lives, the dreams, and the dramas of the twentieth century.

Photography advisor Pinault Collection / Historical consultant "CHRONORAMA"

[…]

Four hundred and nine works, from 1910 to 1979, presented chronologically and by decade, illustrate the men, the women, the moments in history, the daily lives, the dreams, and the dramas of the twentieth century. This retrospective “Chronorama” is also an invitation to introspection of a Western world that has not only recognized the power of images but has invented its own language. If the nineteenth century was the last bastion of the civilization of the written word, the twentieth century was soon to be that of the image. In this way, time and images became inseparable.

These fragments of the past come from an extraordinary resource of exceptional richness: the archives of Condé Nast, partly acquired by the Pinault Collection in 2021. Condé Nast, one of the world’s largest press groups, currently owns twenty-five titles, including the iconic and historic Vogue, Vanity Fair, House & Garden, and the New Yorker.

[...]

A pioneer in the use of color photography in magazines in the 1930s but also in his approach to advertising, Condé Nast revolutionized the international press in several ways. The close collaboration with the artists of his time, which he established from the very beginnings of his empire, is an integral part of the group’s identity and has allowed some of the greatest talents of the twentieth century to emerge.

It is the quality of the works preserved that makes this archive invaluable. Many of the century’s great photographers started at Condé Nast before being exhibited and recognized as core figures within the art market. They saw their first creations in the pages of magazines, ephemeral images replaced the following week by a new issue at a frantic pace. The medium did not, however, affect the quality of these photographed objects. We see this particularly in the work of photographers in the first half of the twentieth century, such as Maurice Goldberg or Edward Steichen. Even if their photograph was intended to be reproduced in a magazine, they treated their image as an art object in its own right. Thus, many of their works were mounted on a support or carefully signed and printed by their creator, as is normally done for a fine art print. This is how a photograph such as Cuzco Children, taken by Irving Penn in 1948, was published in 1962 in Vogue and then exhibited for the first time at London’s Marlborough Gallery in 1977. This double portrait is now considered one of the photographer’s masterpieces.

It is what “CHRONORAMA” aims to show: works in their own right, irrespective of their primary status as visual aids for articles and the magazine.

Magazines were, in turn, the vehicle for this new imagery, which gradually took the place of illustration. The photographs included in the archives were those sent by the photographers to the magazines of Paris, London, and New York. The purpose of these prints was not to exist on their own but merely to transport an image that was to be printed in a magazine. They were accompanied by a text that clarified their meaning or they illustrated the words of an advertisement or an article. It is therefore impossible to deny the original link between the printed magazine and the creation of these photographic objects.

[...]

This exhibition offers a history of the twentieth century through the lens of more than 185 photographers and artists, from the most illustrious—such as Adolf de Meyer, Margaret Bourke-White, Edward Steichen, George Hoyningen-Huene, Horst P. Horst, Lee Miller, Diane Arbus, Irving Penn, Cecil Beaton, and Helmut Newton—to those unknown to the general public. Amongst portraits of stage and screen icons and great personalities of the century, we find fashion photography, photo reportage, architectural photography, still life, and documentary photography. Within this visual mosaic are masterpieces of photographic art alongside never-before-published images. These glossy treasures embody a certain, inescapably subjective vision of history. They represent a Western cultural and financial elite.

[...]

This journey, where we observe the decline of illustration in favor of photography, is also a history of aesthetic evolution through the decades. Indeed, whether they are changes in taste in clothing, architecture, décor, or artistic revolutions, all these mutations infuse the works presented in this exhibition. Cubism influences the costumes and wardrobes of European socialites, the Neoclassicism of the interwar period stands out in the once-again corseted female silhouettes, Art Deco is everywhere, particularly in the architecture of the great capital cities, while colorful scarves and miniskirts are the expression of the sexual liberation of the late 1960s. These magazines make the spirit of the times visible by catalyzing the aesthetics of the moment, whether they are avant-garde or simply “in.”

[...]

To these visual alterations of the image are added the material alterations of the object. Scratches, folds, stains, missing parts, and versos awash with stamps, markings, and annotations: all these manipulations, required for publication, gave these works their historical strength. These are the real stigmata of their circulation, these marks of time, which are both the scars and essential conditions by which we recognize them. We are ultimately faced not only with an image but also an imprint, which carries within it its lived history, mimicking the example of our skin, which bears the marks of our own history. These photographs, created within a precise context, reworked so that they take on new life, find other uses and meanings. Indeed, they can be represented in alternative contexts with additional manipulations. The print passes from hand to hand, gets damaged, and wears out, but the image endures and proliferates. Its materiality withers as its immateriality grows. This peculiar process is already part of the mental consumption of our time, where photographs can be completely detached from their physical form. Nowadays, photography seems close to perfecting a process of ultra-democratization that makes it accessible, immediate, and free, and where the collusion between the image and its viewer is everything.

This exhibition allows us to relive a kind of golden age of photographic art. “CHRONORAMA” is, at a time when millions of images are produced every minute and instantly shared, of definite importance in its role of transmission to this and future generations. The exhibition, presented by the Pinault Collection, focuses on the prolific culture of photography in the last century, before the advent of digital technology. By sharing this collective imagination, the exhibition perpetuates and sometimes even resurrects these works: they are once more published, shown, and related to new images. Exhuming these photographs from the archives is to add another chapter to their history and allow younger generations to approach this medium in its own materiality as either an aesthetic object, a communication tool, or even as a storyteller.

[…]

The archive is a time capsule that remains with us today; “CHRONORAMA” is intended as a final panorama, a gallery of men and women in their heyday whose memory will soon be available through images alone, their contemporaries and witnesses having faded away, quietly, with the passing of time.

Matthieu Humery and Andrew Cowan

Excerpts from the catalogue of the exhibition “CHRONORAMA”